Visited by a muse in his dreams, Smith turns to some of his favorite cooperative gaming experiences for influence as he designs Spaceteam.

Everybody Shake! The Making of Spaceteam

Written by David L. Craddock

Table of Contents

Chapter 2: Like a Bad Episode of Star Trek

Best-laid Plans

Upon awakening from his cardboard-cabinet-lined Arcadia, Henry Smith wasted little time mapping out his new design—chiefly because he had little time to waste. His goal was to crank out a small game in a relatively short time before moving on to one of his loftier designs. The concept he’d literally dreamed up seemed the perfect lab rat: a cooperative game where each player got his or her own screen that displayed a menu full of commands and an instruction at the top that could only be carried out by one of them.

“The idea came to me, and it seemed simple enough that I could build something off of it,” he explains. “I gave myself such a short deadline that I basically couldn’t make it more complex than having instructions on one person’s screen, and someone else was following it. That sort of core, that seed, just sort of sprang from there. I added just enough to make it a fun, playable experience. I had to leave out some ideas I had, but I think that was for the best; if I’d made it more complicated, it wouldn’t be as accessible as it is.”

With the seed of a design in hand, Smith contemplated the soil in which it should be planted. Hallmarks of Shipshape, his previous game design, made for fertile earth. Players would share captaincy of a spaceship, and there would be disastrous goings-on that thwarted their progress. The twist was that players would work as a team not to build their ship, but to hold it together. Spaceteam seemed a fitting title for the game, and the iPhone seemed a fitting platform.

The business of developing and selling games had undergone a radical shake-up during Smith’s time working for mega-publisher BioWare, and Apple’s iPhone was at the epicenter. The advent of the App Store in July 2008 had transformed the touchscreen-based phone from a futuristic yet utilitarian phone/web browser, into the most dynamic piece of technology in extant. Through it, users could log and share data, listen to and record music, get step-by-step directions via GPS apps, read eBooks, and even film videos replete with special effects. Moreover, anyone with a Mac and a knowledge of programming could write an app and sell it on the App Store.

Above all, the App Store was a bottomless well of games. Apple had rolled out the App Store for iPhone and iPod touch in July 2008. That December, Apple celebrated the addition of its 10,000th user-created app. Three and a half years later, in the spring of 2012, the App Store hosted hundreds of millions of user accounts and hundreds of thousands of apps. According to statistics, games outpaced every other category of application by a wide margin.

Apple’s phone was only one new-fangled way to play games. On other platforms, independent authors were experimenting with new ways to use conventional input devices. From his tiny apartment in Harlem, Doug Wilson, a PhD student at University of Copenhagen in Denmark, designed Johann Sebastian Joust (J.S. Joust) around Sony’s wand-like PlayStation Move controller. Each player must hold his or her wand still while other players try to bump them. There are no graphics; J.S. Joust doesn’t even require a screen. Smith tried it and was impressed as much by how the wand had been repurposed as by the game itself. “I realized we’ve got this amazing technology in our pockets, but also in our game controllers and peripherals, and there’s so much we could be doing with them. We could connect them together, we could hide information from people, we can press buttons on them. I knew there was something new we could do.”

To cap things off, the App Store’s price points matched Smith’s expectations for his one-month project. Many games cost between $5 and 99 cents, but a growing number were available for free. To Smith, “free” seemed the ideal price tag for Spaceteam.

“Originally, it was just going to be this one-month practice project, so I didn’t think it would be worth paying for, really. It would only be a few weeks’ worth of work, and I figured making it free would help with my exposure; I’d be able to get it in front of more people because I didn’t expect it to make money, so why bother charging for it at all?”

Making Magic

Smith knew that control panels would lie at the heart of Spaceteam. Given their importance, and his years of experience designing interfaces, he placed the highest priority on the composition of the panel as well as how users would learn to interact with it. The learning process began not in a tutorial level, or even the first level, but at the title screen.

Spaceteam’s title screen defines simplicity. Colored objects, maybe stars, whiz by in the background. At the top, the game’s title is displayed just below a stylized ST logo. Beneath it is a dial labeled Play. To get started, players must touch the dial and turn it. Smith chose a dial—conceivably opposed to a traditional button labeled Start—intentionally.

Spaceteam’s title screen defines simplicity. Colored objects, maybe stars, whiz by in the background. At the top, the game’s title is displayed just below a stylized ST logo. Beneath it is a dial labeled Play. To get started, players must touch the dial and turn it. Smith chose a dial—conceivably opposed to a traditional button labeled Start—intentionally.

“Because my background is in user interface design, I thought about this stuff a lot. Even from the title screen, instead of having a button to play, there’s a dial you have to turn to start the game. I think a lot of people probably just see that as a gimmick, but that was really important to me, to have a dial there, because that’s the most complex control in the game. There are sliders and buttons and switches, and people are already familiar with dials as well, but the dial is the most complex control [in Spaceteam], and so I wanted you to be able to use the dial; I wanted you to understand how it worked and know what to do when you saw another one—even before the game started.”

Turning the dial transports players to a waiting room, where their avatar, a vaguely humanoid figure bedecked in colored apparel and possibly sporting antennae, tusks, or other appendages, stands idle. Other avatars appear as players pop in over WiFi or Bluetooth. Each player should notice a single button at the bottom of the screen. Tapping it causes their avatar to raise its hand and fire laser rings into the air. Release the button, and the rings taper off.

The first time they become part of an eponymous space team, players are likely to stand around giggling as they fire colored rings into the sky, and then peer around at each other in confusion. What exactly, they might ask, is the point? What are they supposed to do? Eventually, they stumble upon an exciting discovery: by firing rings at the same time, they can exit the lobby and begin playing.

“I do get the occasional email where people tell me, ‘I can’t get out of the waiting room,’ and I have to explain it to them. But the idea is that, eventually, they’ll figure it out. Not only will that realization itself be sort of a fun experience, but they’ll help each other out: ‘Oh, I shoot the beam when I press this button, so maybe we all have to shoot the beams together.’ You naturally help each other, because if one person doesn’t get it, they’re going to slow everyone from progressing.”

Thus, the stage for Spaceteam is set. By feeling their way through the title screen and lobby, players know everything they need to play the game proper, before the game gets officially underway. They have mastered its most complex mechanism, and they know, or at least suspect, that they must cooperate to succeed. Smith was intent on crafting a game in which teamwork was the only way to triumph. That motivation came, in part, from Galaxy Trucker, one of few board games (at the time) designed around cooperation rather than competition.

“One of the motivations was to make a game that worked like that because I love that dynamic: I love playing board games with my friends. You hear all this talk about social gaming, but it’s not really social, right? You’re just sending people Facebook ‘likes’ or helping someone with their farm, but you’re not really communicating with them. I wanted to make something that was a bit different.”

Smith’s decision to craft intuitive, self-guided tutorials for Spaceteam went above and beyond the cleverness of his implementation. More than shooting bad guys and setting high scores, he loved the sense of discovery that games could incite. While crafting Mass Effect 3’s UI at BioWare, he had done his best to avoid tidbits pertaining to the galaxy-spanning story, going so far as to duck out of team meetings when colleagues showed off plot-heavy assets like the movie that plays when players finish the game. He’d wanted to go into ME3 fresh. That passion for self-guided discovery should be transplanted into Spaceteam, he decided.

Most tutorials conspired against that desire. Rather than let players take their first steps more or less on their own, only lending a hand where needed, modern games tend to assume their audience needs (and perhaps wants) everything explained for them up front. To that end, games inundate players with information, burying them beneath giant walls of text and semi-interactive segments that cause the pacing to stumble right out of the gate.

“If a game starts off, and the first thing it does is show you a giant wall of text, people don’t read those things; they just click through. So they’re not even performing the function [the designer] wants them to perform. Even if they do read it, it’s not nearly as fun to read instructions about what to do as it is to discover it for yourself. Even if your game is really complicated, you can introduce people to features gradually like that, so they can gradually discover more and more about the user interface and the interactions in the game design.”

Continuing, Smith says, “I think we need more discovery in games as a whole. We teach people what to do way more than we should. It’s magic to discover things on your own.”

Stabilization

Onward and upward. From dialing in on the title screen to filling the air with more colored rings than Gandalf the Grey, players beam up and into their spaceship. Before them, on their iDevice of choice, they behold a control panel cluttered with a unique assortment of buttons, knobs, and dials. At the top of each screen, a different command materializes: turn this dial from off to on, bump that slider from 0 to 2, flip this switch to such-and-such position. Players search their screen; if they don’t see the appropriate mechanism on their panel, they must verbalize the command so their group knows to scan their layouts.

To keep the experience fresh, Spaceteam randomly generates the names of the apparatuses on each player’s screen. Some elements might show up every so often, giving players a reason to tell their friends about an amusingly named component they remembered from an earlier session. Some are new. Most, like vibropuffer and flangeram and pi-snorkel, are utterly ridiculous and entirely fictional.

“I already had a system for generating random planet names and galaxy names because I wanted to build this procedural universe [in Shipshape],” says Smith, “so I repurposed that system to generate the technobabble that you have in Spaceteam, which is basically just like a bad episode of Star Trek. A lot of it just sort of fell out of that. It kind of built itself from there because there were all sorts of pieces that it just made sense to have in that universe once that framework was up.”

If players could win merely by spinning dials and flipping switches, the novelty of Spaceteam would swiftly wear thin. Smith foresaw such tedium, and circumvented it by looking to a production trick used on episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation. In battle scenes where the Enterprise comes under attack, Captain Kirk and the crew aboard the vessel lurch around each time their ship is struck, and the on-screen image shudders to draw viewers into the action. The effect is produced using Hollywood’s trademark movie magic.

“When the cameraman tells you to shake, you all kind of move around in your chairs as if the whole [ship] is shake, but in fact it’s just the camera shaking,” Smith says, laughing. “Someone actually has a video online that I love, which is a snippet of Star Trek where the crew on the Enterprise is shaking like that, but they run an image stabilization filter on that so the image doesn’t shake, so you just see Patrick Stewart rocking around in his chair. It’s hilarious.”

Rudimentary, but effective at drawing viewers into the intensity of the moment. Smith reproduced the effect in Spaceteam by introducing asteroids. While players busily shout out instructions and tap their phones, the message ASTEROID! (everybody shake) arbitrarily appears on every screen, and remains until players shake their devices in unison.

Asteroids are one type of randomly occurring disaster. Others abound, and all capitalize on Smith’s desires to bring the iPhone’s hardware to bear. Shaking to dodge an asteroid triggers the phone’s accelerometer, the component responsible for measuring acceleration. The accelerometer comes into play again when wormholes appear, swallowing control panels and instructions in a vortex-like distortion effect. Flipping the device clears the screen. Other effects, like slime, sparks, and panels that pop loose, are simpler. stick panels back into place by swinging them into position and holding them steady for a moment or two.

Covering the screen in muck played into Smith’s desire to craft an intuitive UI. When users see a smudge on their touchscreen, their first thought is to wipe it away. Fixing panels is trickier: players must slide them back into place and hold them steady for a moment or two. “The dangling panels were also really important because the entire game’s user interface is just buttons and dials and sliders. I wanted to bring this chaos into it where everything is going crazy. I wanted part of that to be fighting with the interface itself: the interface is actually falling apart. It just made sense with the engine, because it had a physics engine built in, so I could take advantage of gravity, and attach things, hinge joints and stuff. It was really easy to add, and I think it made a lot of sense in the fiction of the game.”

Those moments become more and more precious as players advance. With each level cleared, Spaceteam fires out instructions and special events at an increasing rate, going so far as to stack asteroids and wormholes so that players must frantically shake and flip their devices before hastily returning to screaming instructions to the room at large. It’s natural, even likely, that what turned into a mild-mannered session of play around a card or kitchen table, with players relaying instructions calmly, escalates into a shouting match, each player struggling to be heard over their teammates while simultaneously twisting and turning and shaking their phones.

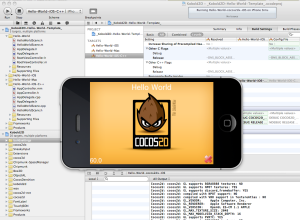

Smith was pleased by how much events like wormholes added to the Spaceteam experience. As a bonus, visual effects like screen distortion and wobbling were painless to render. “The game engine I’m using, cocos2d, happens to have a bunch of these full-screen effects that ship right out of the box—warping the screen, doing ripples, wobbling or whatever. I knew they were there, and I wanted to use them; they’re cool effects.”

Waiting Room

Smith misjudged Spaceteam. As much as he had been smitten by the idea from the moment he’d dreamed it, the game’s main appeal had been its development cycle. A few control panels, some whiz-bang special effects baked into his engine of choice, and only four weeks withdrawn from the fifty-two he had banked for solo game development.

Smith misjudged Spaceteam. As much as he had been smitten by the idea from the moment he’d dreamed it, the game’s main appeal had been its development cycle. A few control panels, some whiz-bang special effects baked into his engine of choice, and only four weeks withdrawn from the fifty-two he had banked for solo game development.

Not far into the process, he had to admit that Spaceteam was, yet again, bigger and bolder than he’d intended. But not by much. “Spaceteam was my one-month project, although I think it ended up taking three months,” Smith reflects. “But that was the idea: it was going to teach me how to do iPhone games, and I’d learn how to use the App Store, and I’d have something to point out to people and say, ‘This is something I did. Now buy this awesome game that I’m working on where you buy spaceships.'”

Smith was ecstatic. What had started as more of an experiment than a proper game had evolved into a passion project. Spaceteam was something special; he was certain of that. The next step was to convince a jury of his peers.

**

If you enjoy Episodic Content, please consider showing your support by becoming a patron or via a one-time donation through PayPal.

Preview for Chapter 3

When his first and second playtests goes awry, Smith scrambles to right Spaceteam’s course before he begins exhibiting the game at trade shows.

Bibliography

* That December, Apple celebrated the addition of: http://appshopper.com/blog/2008/12/03/10000-iphone-apps-now-available-on-app-store/

* Three and a half years later, in the spring of 2012: http://mashable.com/2012/06/11/wwdc-2012-app-store-stats/#f2TXd27jbGqh