As Paul Dini teams up with Rocksteady writer Paul Crocker to shape Arkham Asylum’s story, the rest of Rocksteady’s developers take aim at defining the game’s look, feel, and ambiance.

Welcome to the Mad House: Building the Padded Walls of Batman: Arkham Asylum

Written by David L. Craddock

Note: This retrospective has been revised and expanded since its original publication in the June 2015 issue of RETRO Videogame Magazine.

Table of Contents

Chapter 2: If These Walls Could Talk

Rogues

Jim Lee’s Batman as seen in Hush (2003).

In developing Batman: Arkham Asylum, Rocksteady Studios had the blessing of both DC Comics and Warner Bros. to build their own take on the Dark Knight Detective. Nevertheless, they had no intention of reinventing the wheel. Various adaptations of the character from all across popular culture supplied the mortar that bound the bricks of Rocksteady’s madhouse.

Grant Morrison’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, Batman: The Animated Series, and the numerous big-screen variants were only some points of reference. To peel back the layers of Batman’s mask, the developers mined years of stories such as The Killing Joke, a revered story that sees The Joker kidnap and cripple Barbara Gordon; and Hush, a celebrated 12-issue miniseries in DC’s main Batman book illustrated by seasoned comic artist Jim Lee.

“Jim Lee’s Batman was a strong starting reference point as how Batman should look in the game: a muscular, trained and strong character that wouldn’t feel out of place in extreme combat situations,” explained David Hego, art director on Arkham Asylum, in a 2009 interview.

Borrowing liberally from Jim Lee’s vision, Rocksteady’s Batman was a character in his prime: chiseled and powerfully built, his spandex bulged with muscles on top of muscles, forming the archetypical superhero stature. Hego complemented Batman’s over-the-top physique by grounding his costume in reality. He designed the suit with a military motif, weaving together realistic fabric textures and fine details like rivets that fused adjacent armor plates.

Concept art from Batman: Arkham Asylum.

“We went for the dark grey and black costume to stay close to the latest iterations of the comic versions,” Hego explained in 2009. To nail the character’s iconic look, Hego and his team of artists collaborated with the veteran illustrators at WildStorm, a comic book imprint founded by Jim Lee in 1992. “I would say that there was been between 10 and 15 concepts of Batman before we started settling on his final look.”

Batman’s aesthetic straddled comic-book fantasy and reality, a look that informed Arkham Asylum’s visual direction as a whole. Hego aimed to imbue Arkham Asylum with hyperrealism—absurd in some respects such as character physique, yet lifelike in nuts-and-bolts details like costume accoutrements and fluid animation.

Batman’s aesthetic straddled comic-book fantasy and reality, a look that informed Arkham Asylum’s visual direction as a whole. Hego aimed to imbue Arkham Asylum with hyperrealism—absurd in some respects such as character physique, yet lifelike in nuts-and-bolts details like costume accoutrements and fluid animation.

“One of the big advantages of the stylized realism was we were jumping across the uncanny valley,” Hego said at the 2010 Develop conference. “By making [the characters] so stylized, you can forget about uncanny valley because you accept that it’s not real.”

A hero is only as interesting as his or her villains, and most pundits agree that Batman’s got the best rogue’s gallery in all of comic-book-dom. “There are just so many characters that there’s no way we’d be able to get all of them in properly,” senior gameplay programmer Paul Denning told Games Radar in 2009. Joker was a shoe-in. Others such as the Mad Hatter, who Paul Dini envisioned lying in wait for Batman at the center of a hedge maze on the asylum grounds, were left behind on the drawing board.

“Once we got the initial design underway, we were looking at characters that could test Batman,” Denning said. “A lot of the villains we used can better Batman in their core disciplines. Bane beats Batman in terms of brute strength, and The Riddler is smarter than Batman. But they are all very flawed as well. So, if you can’t take them on in their strongest area you can certainly take them on in another way—so that’s where the gameplay ideas originated from.”

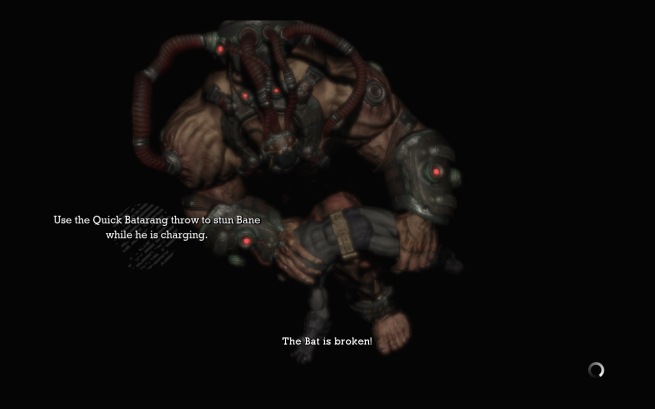

Bane is perhaps Rocksteady’s poster villain for the hyper-realistic visual style the team developed for Arkham Asylum. An intimidating physical specimen in the comics—infamous for snapping Bruce Wayne’s spine over his knee like a dry twig in DC’s landmark Knightfall storyline—Bane is a behemoth in Rocksteady’s game. He towers over Batman, easily two to three times the Dark Knight’s size, and lumbers around dishing out monosyllabic taunts. He is, another words, a pure bruiser, which some fans of the character probably didn’t appreciate.

The cadre of Bat-experts at Rocksteady were aware that some of their interpretations would fail to meet expectations. “Our iteration of Bane is maybe not what you expected from the comics,” admitted Denning back in 2009. “In the comics he’s very, very intelligent. We obviously didn’t go down that route. If you did, you’d need a lot more screen time to convey that.”

The cadre of Bat-experts at Rocksteady were aware that some of their interpretations would fail to meet expectations. “Our iteration of Bane is maybe not what you expected from the comics,” admitted Denning back in 2009. “In the comics he’s very, very intelligent. We obviously didn’t go down that route. If you did, you’d need a lot more screen time to convey that.”

Although Rocksteady did not want to tie the game to any one mythos, they made the wise and popular choice to hire many of the voice actors from Batman: TAS. Among other returning talents, Kevin Conroy reprised his gruff and grating Batman, Mark Hamill’s gleeful and maniacal Joker laugh rang through the studio, and Arleen Sorkin reassumed the persona of Harley Quinn, The Joker’s curvaceous henchwoman—a character created by Dini for TAS, and who proved so popular that DC weaved her into the tapestry of the comic books.

“As we have to keep the game moving, there wasn’t much of a chance to explore the more adult Harley’s personality, outside of brief scenes with Ivy and in some of the recorded sessions with the Joker,” Dini says. (Quinn took center stage in Harley Quinn’s Revenge, a DLC expansion for 2011’s Batman: Arkham City.)

For the Joker, David Hego explained that “We took the interpretation of The Joker from the Killing Joke comics and started iterating from there.” Early concept sketches showed the character wearing the Glasgow smile, a deep cut that curves from a victim’s lips up to their ears—and a look worn to inimitable effect by Heath Ledger in 2008’s The Dark Knight. The artists ultimately decided their Joker looked too much like Ledger’s, and compromised by painting on a Glasgow-like smile with lipstick rather than a knife.

Hamill slipped comfortably back into his playful yet sociopathic interpretation of the Joker, even going so far as to get into character the same way he had during work on Batman: TAS. During the cartoon’s heyday, he had workshopped Joker by studying character sketches drawn by the show’s art team. Hamill followed the same process during development of Arkham Asylum, blending his quirks and characteristics with concept art provided by Rocksteady’s artists.

“Working with Kevin [Conroy] and Mark [Hamill] was amazing,” Hill told Eurogamer. “We knew from day one that we wanted them. Mark delivers an awesome performance as the Joker. He’s a deadly sociopath while being extremely charismatic and funny. It’s a really enjoyable combination! We actually went away and wrote a ton of new lines for Mark after the first session because his performance was so good.”

Cinematic Storytelling

Paul Dini collaborated with Rocksteady writer Paul Crocker to assemble Arkham Asylum’s narrative. At the game’s outset, a short cinematic follows Batman as he drags Joker back to the asylum from which he recently escaped (yet again). The intro is short, only a few minutes long. That, Rocksteady’s principals explained, is by design.

“I think cutscenes should be used to advance the story and display the relationships between characters—things that can’t be done within the action,” said Hill to Gamasutra. He went on to explain that cinematics can and should be utilized to further relationships between characters. Exciting bits, however, should be entrusted to players to perform whenever possible.

“For Batman, we really wanted the cutscenes to advance the relationships between the characters. There were situations where we felt we needed to do that, but we didn’t want the cutscenes to display big action sequences that you wouldn’t assign to the player. When you get that kind of thing, it really disengages you, because you feel like, ‘Why aren’t I able to do that? That’s what I want to do. That’s why I’m holding the pad!'”

Once inside Arkham, players are given control of the Batman. To be more precise, players become the Batman. Tilt the analog stick forward and he strides confidently down a long, run-down corridor. His cape, composed of over 700 animations and dozens of sound bites that took a single artist nearly two years to complete, flutters and flaps behind him depending on particular movement animations; his boots bite into the cracked concrete. Spin the camera around and players get an eyeful of Batman’s stony visage, unruffled inmates leaning through cell bars to taunt and jeer at him.

Just ahead, the throng of police officers and Arkham guards escorting The Joker, strapped to a gurney that rolls along in front of you, board an elevator. Batman joins them. The lights flicker, and players hear a fading hum as the power cuts out. The screen goes black; The Joker’s deranged laugh cuts through the darkness and panicked cries of the guards. A second later, the power snaps back on. Guards scramble and shout, trying to restore order and find their courage. Batman, of course, has the situation well in hand.

“The whole first scene with Batman dragging the Joker into Arkham was a lot of fun. It seemed very natural to me that when the lights go out, Batman instinctively grabs Joker by the throat,” Dini recalls.

The jump from in-game cutscene, depicting Batman’s hand wrapped around Joker’s throat, back to the action is seamless. A ding sounds, the elevator doors open, and Joker’s escort wheels him out into a hall. The player, back in control, is free to follow.

“It was smoke and mirrors in a lot of places,” Denning told Games Radar in regards to Asylum’s scant supply of cutscenes, “but we were very keen to keep the player immersed as much as possible. In Resident Evil 5 there are moments where you’re playing and you find yourself in a completely different place and you think: ‘Well, hold on. I wasn’t really here—you’ve just cheated to get me here,’ and we really didn’t want that.”

Minutes later, The Joker puts his master plan into action. He overpowers his guards, regroups with Harley Quinn, and takes control of the asylum. At her beau’s command, Quinn throws a switch that opens every cell in Arkham Asylum.

These quick cuts between gameplay and cinematics crystalize the player’s objective: Round up the inmates with extreme prejudice before they can get off the island and plunder Gotham.

“Each of the cutscenes is designed in a way that they all change the values of the game,” Hill told Gamasutra. “They all change the value of what you’re doing at any particular time. Never in Batman should you watch a scene and find what you’re doing has not changed, or the importance of your actions has not changed in any way. You learn something new that makes you think about the story in a different way or want to do something in a different way. It’s quite easy to write a lot of scenes on paper, but they’re not affecting the play experience. We really wanted the cutscenes to do that when you played the game.”

“And at the End of Fear…”

Haunted houses play a pivotal role in haunted-house stories. Every room, every parlor, every passageway, must drag you deeper into the atmosphere and story until the creepy grounds feel as familiar to players as their own home. In Arkham Asylum, Rocksteady crafted a memorable house of horrors through environments designed around a patchwork of visual styles and techniques.

Haunted houses play a pivotal role in haunted-house stories. Every room, every parlor, every passageway, must drag you deeper into the atmosphere and story until the creepy grounds feel as familiar to players as their own home. In Arkham Asylum, Rocksteady crafted a memorable house of horrors through environments designed around a patchwork of visual styles and techniques.

“The first main goal while designing the visual direction of Batman: Arkham Asylum was to work on a glue that would join two diametrically opposed styles: the comic-book style and an ultra-realistic render,” Hego explained in a 2009 interview. “The traits of the characters and the environmental architecture had to be extravagant enough to embrace the essence of the Batman universe, but at the same time we wanted to give the game a very realistic touch in the texture treatment and in the details. Everything had to feel consistent and in a sense ‘real.’ The second goal in the art direction was to recreate the dark and gothic feel that is inherent to the Batman universe in general and Arkham Asylum in particular. We wanted the game as dark as possible to really suit the twisted mood and atmosphere of the asylum. The building by itself had to feel as insane as the lunatics it holds.”

Drawing from real-life locales such as Alcatraz while still adhering to the Gothic, gritty themes that form the backbone of Batman lore, Hego and the art team divided the singular Arkham Asylum building from the comic books into a handful of crumbling edifices connected by a spread of rolling lawns, wet cliffs, and derelict sewer tunnels. Restricting their game to a tight span of real estate let Rocksteady embrace a less-is-more approach. By limiting the locales players can explore, the artists were able to infuse each area with a distinctive atmosphere and personality.

“As Arkham Asylum is composed of several different buildings, we worked on different architectural styles to make the place believable and add a layer of history to each location,” Hego told Comic Book Resources in 2009. “For example, while the administration building—the historical Arkham mansion—is designed with a high gothic architecture style in mind, the medical aisle is more inspired from a Victorian architecture and metalwork structure. On the other hand, the intensive treatment unit is composed of a strong industrial gothic architecture and the catacombs hearken of an early 20th-century brickwork and industrial Victorian era.”

Each area is saturated in unique colors and lighting. The medical building, which houses examination rooms and the morgue, is made up of wide, sterile hallways and tiled floors, and exudes a range of chilly blues and fluorescent whites. Conversely, the penitentiary’s corridors are dark, narrow, and circuitous, lined with cramped cells and electrified floors. The grounds, the webbing that ties the Arkham estate together, teems with greenery and earthen paths.

Sensory props such as stone gargoyles and bloodstains, and The Joker breaking in over the PA system to taunt Batman (or his own minions), punctuate environs nicely and serve a function beyond mere set decoration. Gargoyles, perched high up around rooms where stealth encounters take place, give players a perch on which to espy the terrain and formulate a plan of attack. Joker’s mockery, loud and booming from the speakers mounted in every room, clue players in to where to go next.

Arkham Asylum’s visuals pull double duty. Artistic elements that exist in inverse proportions, such as light and shadow, and hot and cold colors, are used to draw the player’s eye, and ensure they did not grow bored or complacent with any color palette. “A brown and monochromatic color palette is often overused to depict a dark and moody atmosphere,” Hego said in 2009. “This is something we definitely didn’t want to do, as we wanted the game to be as vibrant as a comic book. We used a lot of saturated colors in the lighting while successfully keeping the mood dark and gothic. This was quite a challenge by itself.”

One of the aspects of Arkham Asylum fans enjoy most is stumbling across the holding cells of supervillains. Mr. Freeze’s cryo chamber is lined with ice, Quinn built a shrine to her beloved “Mistah Jay,” and Catwoman’s goggles are on display in an administration wing. Even obscure villains like Calendar Man get their due. For hardcore fans, exploring Arkham Asylum is like embarking on a self-guided tour Batman’s history.

Rather than incur the ire of fans who expect the game to feature every villain, no matter how obscure, Rocksteady secreted every area with a panoply of character biographies, recordings of psychiatric evaluations with various characters, and other Easter eggs.

Dini and Rocksteady’s developers further demonstrated their exhaustive knowledge of the Dark Knight by handcrafting encounters with legendary foes. Killer Croc stalks players through abandoned sewer tunnels and can kill them in a single pounce. Not one to face Batman head on, Riddler taunts the Dark Knight from afar by arranging “riddles” and stashing them around the Asylum. Some riddles ask players to recover neon-green question-mark trophies tucked inside vents and behind walls. Other challenges are actual riddles whose answers point to elements hidden in plain sight—a cache of corpses exhibiting slashed throats, the handiwork of serial killer Zsasz; Mr. Freeze’s ice-covered chamber; Catwoman’s goggles arranged on a stone bust in an office; and a very subtle cameo by the shapeshifting Clayface, who can only be recognized by triggering Detective Vision, a special ability handmade for Arkham Asylum. Riddler stays in touch with Batman over the course of the game and shifts gears from cocky to increasingly incensed as players solve his riddles, going so far as to accuse players of looking up answers on the Internet.

The majority of Riddler’s challenges can only be solved after reaching a certain checkpoint or attaining a specific piece of equipment. Rocksteady’s designers appropriated this style of gated progression from games like Nintendo’s Metroid and The Legend of Zelda franchises. “They were definitely big influences,” creative director Sefton Hill told Gamasutra. “I like that sort of approach to design—giving you a number of different gadgets and abilities that you can use and combine in different ways, and the way that combines and the feeling of being in this complete other world.”

Gated progression accomplishes multiple purposes. Many open-world games are so vast that players feel intimidated rather than enticed to explore. There’s also the possibility that players will burn out on the world—exploring it for dozens of hours only to grow fatigued by the sight of the world map and the realization that the hundreds of side missions they purport to offer are carbon copies of the same handful of mission objectives copy-and-pasted over and over. Arkham Asylum metes out content, only permitting players to access new areas after completing specific objectives in order to prevent them from feeling overwhelmed and petering out.

More importantly, Arkham Asylum is by no means a small game, yet it is intimate enough that players quickly come to know their way around its aqueducts, pathways, and halls. That sense of familiarity promotes a bond between players and the island. Every locale is original and idiosyncratic. Every corridor, great hall, and side passage teem with secrets—many in sight but just out of reach, a surefire way to persuade players to return and continue poking around once they have added more gadgets and abilities to their repertoire.

“Oblivion”

To make sure players never felt too comfy and cozy in the game’s warrens, Rocksteady’s designers transplanted every Batman fan’s favorite boogeyman into Arkham Asylum. At three junctures, players get pulled into nightmarish visions triggered by Scarecrow’s fear toxin. Each blurs the line between in-game reality and Batman’s already-sensitive psyche, and culminates in a stealth sequence where players must sneak past a giant-sized Scarecrow without being seen.

The first, and most chilling, takes place in the morgue area. Entering the room, players spot three body bags on tables. Unzipping the first two reveals the corpses of Bruce Wayne’s parents, who whisper that he has failed them. Players cannot leave until they have unzipped the third, revealing the most ghoulish incarnation of Scarecrow yet—a gangly hooded figure wearing a gas mask and syringes for fingers.

The second nightmare sees players walk down a long, dimly lit corridor that gradually shifts and warps into the alley where Bruce Wayne witnessed his parents’ murder. This one remains a favorite among Rocksteady’s developers, and plays out in accordance with the team’s directive that cinematics should advance story and character relationships without taking players out of the action.

“At the very end when you become young Bruce Wayne, it looks like it’s all scripted and sequence based, he’s crouched down over his parents and nothing happens,” Denning told Games Radar. “Then you realize that if you push a button you’re still in control—and you then walk off. That was a really powerful scene and we really enjoyed putting that together.”

For the third and final Scarecrow confrontation, Rocksteady saved the best for last. After performing an innocuous action, a glitch freezes the player’s PC or game console. Or at least, that’s what they’re supposed to think. A few moments later, the screen goes dark, and the game flips the script and reconstructs the opening cinematic, but with Batman being hauled to Arkham Asylum by the Joker.

“The funny thing was we focus tested it and people didn’t get it,” Denning admitted to Games Radar. “They didn’t understand what had happened and this was when we had the cutscenes in. Even when they saw the cutscene with The Joker driving the Batmobile they just said: ‘Oh – that looked like something went wrong there!’ So, we were really worried at one point that it wasn’t going to come off. The other thing was we weren’t sure whether Microsoft and Sony would allow it because obviously it made it look like your machine had crashed. Honestly though, we have to bow our heads a little bit to Eternal Darkness, they paved the way by doing that a number of years before. If you ask people what the key moments were—most of them will mention that. The trouble is that it’s a bit of a one shot mechanism. Once you’ve done it once, people expect it. You’ve really got to nail it the first time or we’ve effectively lost. It had to be once and it had to be good.”

Scarecrow’s nightmares, and Arkham Asylum as a whole, were grim and unsettling—exactly what Dini and Rocksteady wanted to achieve. “The consensus was to make the game, and thereby the world, more dangerous, and more adult,” Dini tells me.

But fans know that the Batman is unfazed by danger. Quite the contrary. Thanks to the plethora of wonderful tools at his disposal, he flirts with danger, dispatching even the most bloodthirsty psychopaths without breaking a sweat.

The trick, Rocksteady’s developers knew, was constructing a method of combat that enabled players to tap into Batman’s talent for effortless violence.

**

If you enjoy Episodic Content, please consider showing your support by becoming a patron or via a one-time donation through PayPal.

Preview for Chapter 3: Whether skulking through shadows or out in plain sight, Rocksteady’s Batman chips away at Joker’s henchmen (and their skulls) through elegantly designed combat, stealth, and forensic systems.

Bibliography

* Jim Lee’s Batman was a strong starting reference point: “The Art of Batman: Arkham Asylum.” Comic Book Resources. http://www.comicbookresources.com/?page=article&id=21959.

* We went for the dark grey and black costume: Ibid.

* Hego and his team of artists collaborated with the veteran illustrators at WildStorm: Ibid.

* One of the big advantages of the stylized realism: “Arkham Asylum art director on rebooting Batman.” http://www.gamespot.com/articles/arkham-asylum-art-director-on-rebooting-batman/1100-6253531/.

* There are just so many characters that there’s no way: “Looking back at Batman: Arkham Asylum.” http://www.gamesradar.com/looking-back-at-batman-arkham-asylum/.

* Once we got the initial design underway: Ibid.

* Our iteration of Bane is maybe not what you expected from the comics: Ibid.

* As we have to keep the game moving, there wasn’t much of a chance to explore: Interview with Paul Dini. Unless stated otherwise, all quotes attributed to Paul Dini come from our interviews conducted in 2015.

* We took the interpretation of The Joker from the Killing Joke: “The Art of Batman: Arkham Asylum.” Comic Book Resources. http://www.comicbookresources.com/?page=article&id=21959.

* Working with Kevin [Conroy] and Mark [Hamill] was amazing: “Batman: Arkham Asylum.” Eurogamer. http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/batman-arkham-asylum-live-q-and-a.

* I think cutscenes should be used to advance the story: “Rocksteady’s Sefton Hill Unmasks Batman: Arkham Asylum.” Gamasutra. http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/132540/rocksteadys_sefton_hill_unmasks_.php.

* For Batman, we really wanted the cutscenes to advance: Ibid.

* His cape, composed of over 700 animations: “Batman Arkham Asylum – Did You Know Gaming? Feat. WeeklyTubeShow.” Did You Know Gaming?. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nPYBTPBlG30.

* It was smoke and mirrors in a lot of places: “Looking back at Batman: Arkham Asylum.” http://www.gamesradar.com/looking-back-at-batman-arkham-asylum/.

* Each of the cutscenes is designed in a way: “Rocksteady’s Sefton Hill Unmasks Batman: Arkham Asylum.” Gamasutra. http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/132540/rocksteadys_sefton_hill_unmasks_.php.

* The first main goal while designing the visual direction: “The Art of Batman: Arkham Asylum.” Comic Book Resources. http://www.comicbookresources.com/?page=article&id=21959.

* As Arkham Asylum is composed of several different buildings: Ibid.

* A brown and monochromatic color palette is often: Ibid.

* They were definitely big influences: “Rocksteady’s Sefton Hill Unmasks Batman: Arkham Asylum.” Gamasutra. http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/132540/rocksteadys_sefton_hill_unmasks_.php.

* At the very end when you become young Bruce Wayne: “Looking back at Batman: Arkham Asylum.” http://www.gamesradar.com/looking-back-at-batman-arkham-asylum/.

* The funny thing was we focus tested it and people didn’t get it: Ibid.