Forays into the woodland around his childhood home inspire Shigeru Miyamoto to create one of gaming’s most legendary franchises.

Hyrule Fantasy: The Power, Wisdom, and Courage of The Legend of Zelda

Chapter 1: Pocket Garden

Author’s Note: This story has been adapted from Making Fun: Stories of Game Development – Volume 1. It is available for purchase in paperback and digital formats.

It’s Dangerous to Go Alone…

Shigeru Miyamoto tried to stay calm.

He’d been exploring the woods in Sonobe, a sleepy town just outside the bustling metropolis of Kyoto, Japan. Exploring was his favorite pastime, and Miyamoto thought himself quite good at it. Every day, the eight-year-old pioneer ventured a little further into Sonobe’s wild countryside. Rice plains gave way to grassy hills. From atop them, he could see his home, a box in a neat grid of boxes, tiny enough to fit in between his thumb and forefinger.

Forging ahead, he followed winding canyons to the Sonobe River. From the river, he hiked up a hillside, swatting idly at tall grass with his stick as the sky grew dark — and that was when his stomach climbed into his throat.

His foot hovered over a deep hole.

Miyamoto peered in. Blackness stared back, threatening to swallow him.

Rising, he turned on his heel and fled back home. Every passage led somewhere, and he meant to follow that one.

But not today. He was not yet ready.1

Monkeying Around

For Miyamoto, born in 1952, nature and creativity went hand in hand. He embarked on fantastic voyages in and around his hometown, pushing deeper and deeper every trip. “When I was a child,” he told author David Sheff for his 1993 book Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered the World. “I went hiking and found a lake. It was quite a surprise for me to stumble upon it. When I traveled around the country without a map, trying to find my way, stumbling on amazing things as I went, I realized how it felt to go on an adventure like this.”2

As he grew older, Miyamoto nurtured his love for exploration and creative expression. When he wasn’t trekking through Sonobe’s untamed regions, he devoured books and scripted puppet shows and dramatic dances. He aspired to become a toymaker, an occupation that would keep both his hands and mind busy. He studied industrial design at Kanazawa Municipal College of Industrial Arts, but had trouble landing a job after graduation.

In 1977, when he was 25, his father called on some of his contacts and arranged for his son an interview at Nintendo, a small company known for producing playing cards that had pivoted to videogames following the yen-gobbling craze surrounding Atari’s Space Invaders in ’75.

Miyamoto interviewed with Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi. A stern man with a keen eye for business, Yamauchi saw potential in Miyamoto and assigned him to help design Radar Scope, a shooter in the style of Space Invaders. When that game failed to gain traction, Yamauchi tapped Miyamoto to repurpose its cabinets by designing a new game. Miyamoto came up with Donkey Kong, an action game published in 1981 where players run, jump, and climb over platforms and obstacles en route to rescuing a damsel in distress from the eponymous ape.

Following the success of Donkey Kong, Yamauchi founded a new department, Research & Development 4, and appointed Miyamoto its manager. Miyamoto and his R&D4 team came up with another single-screen platformer starring Jumpman, the protagonist of Donkey Kong. Miyamoto renamed Jumpman to Mario and gave him an identical brother, Luigi, garbed in green and blue overalls to complement Mario’s red and blue outfit.

The team was eager, but still inexperienced, and not up to the task of developing a project as ambitious as Mario Bros. on their own. Gunpei Yokoi, who would go on to pioneer some of Nintendo’s most popular devices such as the Game Boy, took Miyamoto under his wing. With programming assistance from Yokoi and R&D1, Mario (formerly known as Jumpman, the protagonist of Miyamoto’s Donkey Kong platformer) and his brother Luigi hopped their way into arcades in on July 14 1983, one day after Nintendo released its Family Computer game console, also known as Famicom.

Nintendo futureproofed the Famicom. It played games on interchangeable cartridges, like Atari’s VCS, but starting in 1986 it could be upgraded by way of the Famicom Disk System (FDS). Diskettes boasted greater storage capacity than cartridges and the ability to read and write data, so players could save their progress and pick up where they left off later.

Banking on a bright future for the Famicom and FDS, R&D4 undertook concurrent projects: Super Mario Bros. for the Famicom, and The Hyrule Fantasy: The Legend of Zelda, positioned as the FDS’s killer app.

“We started to work on The Legend of Zelda at the same time as Super Mario Bros., and since the same teams did both games, we tried to separate the different ideas,” Miyamoto explained in a 2003 interview with Super Play magazine. “Super Mario Bros. should be linear, The Legend of Zelda should be the total opposite.”3

Interactive Storytelling

Although Miyamoto directed both Super Mario Bros. and Zelda, he co-designed the latter with R&D1 designer Takashi Tezuka. Tezuka penned a script about a boy who went on a quest to recover stolen artifacts and rescue a captured princess named Zelda, a name known to Miyamoto through his proclivity for books. “Zelda was the name of the wife of the famous novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald,” he revealed in an interview with Amazon. “She was a famous and beautiful woman from all accounts, and I liked the sound of her name. So I took the liberty of using her name for the very first Zelda title.”4

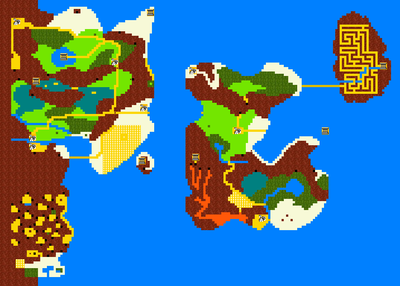

Meanwhile, Miyamoto tried to wrap his head around constructing the fantasy plane of Hyrule. Zelda’s conceit of an open world in which players could go anywhere, do anything, was a bold notion in an era when most games took place on single screens. Displaying action from the side, as in Donkey Kong and Super Mario, seemed a poor fit. A top-down view would work better; more details could fit on the screen, and players would have more control over their character, the boy named Link sporting a green tunic and elfish features. Plus, the larger storage capacity of a diskette would enable him to construct what he referred to as a huge “garden” able to fit in the player’s pocket.

Miyamoto reflected on the adventures of his youth. Together with Tezuka, he stitched together screens comprising a vast wilderness: grasslands, lakes, streams, a mountain range ravaged by earthquakes that sent boulders tumbling down, and caves.

Zelda’s first screen, plains bordered by emerald hills, illustrates the enormity of the adventure. Link starts in the center, a crossroads with paths leading east, north, and west. Just ahead, a cave sits at the foot of a hill. No signposts point out where to go. Players are meant to choose a direction and start walking. When they hit an edge, the next environment scrolls into view.

Along the way, Link finds items to defeat enemies or open up hidden paths, such as bombs able to blow holes in walls, candles with which Link can burn away bushes to uncover staircases, and increasingly ornate swords. Some screens lead to dungeons, subterranean labyrinths and, collectively, another piece of Miyamoto’s boyhood exploits: When he was young, he’d gotten lost in the maze of sliding doors within his family home. He and Tezuka crafted nine dungeons where enemies and new items like a bow, book of spells, and whistle could be found, culminating in a showdown with the evil wizard Ganon.

Each dungeon also contains a shard of the golden Triforce, MacGuffins guarded by boss monsters. Toppling bosses earns players a Triforce shard, as well as a heart container that increases their life energy by one. Other heart containers can be found strewn throughout the land of Hyrule; to reach them, players must step explore and experiment with the tools at Link’s disposal.

As one plays Zelda, it should become apparent that Link is more than a tiny cluster of sprites arranged to form a character. He embodies the fear Miyamoto felt as a boy the first time he wandered far from home… yet curious, too. Likewise, anybody who plays The Legend of Zelda experiences that same cocktail of trepidation and wonder every time they set foot in a new dungeon or forest teeming with bigger, nastier monsters than those conquered in earlier regions.

Over time, Miyamoto’s fear had synthesized with curiosity to form excitement. Each of his adventures had challenged him to experiment, learn, and grow. The heart containers earned by defeating monsters, and the ones collected by uncovering secrets and pushing into uncharted territory, are metaphors for the player’s growing wisdom, courage, and strength. Fortified by knowledge as much as courage, they forge ahead, going further, and further, and further still. Once-terrifying areas become familiar and manageable because players are stronger now than they were before.

Link’s tale of maturation, told not through long-winded cutscenes or excessive dialogue sequences, but through exploration set at a pace of the player’s choosing, is the true narrative of The Legend of Zelda, and it is one of the greatest videogame stories ever told.

Gold Standard

The Legend of Zelda launched alongside the FDS required to play it in February 1986. Eighteen months later, Nintendo prepared to ship it for the Nintendo Entertainment System, the U.S. corollary to Japan’s Famicom. Since the U.S. never received the Disk System, which fizzled quickly in Japan, Zelda would release on a gold-colored cartridge. Lacking disk-based storage, the game saved progress on a lithium battery grafted to the cartridge’s internal circuit board.

Management fretted over giving American players such an open-ended game, and they had good reason. A glut of consoles and substandard software had sent the western console market into a tailspin a few years earlier, culminating in retailers washing their hands of videogames. To maintain the popularity and profitability of the NES, it was vital that audiences feel enabled by Nintendo’s games rather than baffled and exasperated. Zelda ran contrary to that ideal — and strayed even further from it, in fact.

In an early build of Zelda, Link began the game with a sword. When early focus-test groups expressed frustration over finding their way around, Miyamoto did the opposite of what any other executive worried about alienating customers would do. He took the sword away, making the game even harder — and compelling players to communicate with one another when they got stuck, sharing tips and secrets such as the location of the sword, now stashed in the cave on the game’s first screen.

To the astonishment of everyone except Miyamoto, Zelda became an instant classic in the west. Players and critics embraced its blend of real-time combat and nonlinear, make-it-up-as-you-go progression, propelling it to the lofty status as the first NES game to sell over one million copies. Sales continued to soar through 1988, leading fans to assume a sequel must be forthcoming.

They were half right. A sequel already existed; they simply had yet to play it.

Swordplay

By the time R&D4 broke ground on Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, Miyamoto was involved in or supervising the progress of several NES projects in tandem, necessitating that he let others get up to their elbows in directorial duties. He handed over the reins to newcomer Tadashi Sugiyama and stayed on as producer.

Zelda II’s first and most striking dissimilarity to its antecedent is its perspective. Gone is the overhead, bird’s-eye-view camera, replaced by side-scrolling movement not unlike Super Mario Bros. Just like Mario, Link can jump, crouch, and run. Out in the overworld, however, the game reverts to Zelda’s familiar top-down view, leaving players to guide Link along roads, through forests, and into caves and towns.

As players traverse the overworld, enemy silhouettes materialize and give chase. Certain enemies spawn in certain areas, and some areas, such as plains, might pit players against weaker enemies than others, such as swamps. Learning which enemies inhabit which terrain, and maneuvering Link to advantageous terrain before an enemy can tag him, lets players exert some say in when and where battles go down.

Upon colliding with an enemy or entering certain areas, the game switches to a side-scroller, and that’s where Zelda II’s tactical options really open up. Pressing B swings Link’s sword, but enemies like the Iron Knuckle and Stalfos raise and lower their shields, so players must probe for an opening. Other considerations, such as the fact that Link lowers his shield when he swings, and new techniques such as the downward thrust come into play against advanced foes.

Zelda II’s deep swordplay made it one of the more intricate action titles in Nintendo’s prodigious 8-bit library, but other changes hindered the game. Perhaps in an effort to appeal to fans of RPGs like Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest, Zelda II grants experience points for defeating enemies, and spending them increases Link’s vitality, attack power, and magical prowess. Such upgrades are less a preference and more a prerequisite, however. Late in the game, enemies deal so much damage that players feel obligated to farm XP before entering new zones.

The side-scrolling segments, which make up the majority of the game, also prove troubling. In them, the game demands that players perform feats like running over bridges that disintegrate under their feet; dodging enemies that ricochet around the screen as players leap over pits, and bring all of Link’s spells and techniques to bear against exceedingly tough bosses. All that, and players are given only three lives to complete the quest. Die, and they return to the beginning (although shortcuts remain available when players save their progress). Serious fans were up to the challenge, but casual players who had taken to the first Zelda for its emphasis on exploration and easy-to-pick-up navigation found Zelda II less welcoming.

Released on the NES in 1988, Zelda II is considered a black sheep. While it reviewed well, and its combat made an impact on future installments, the use of XP coupled with spikes in difficulty slowed its pacing, a sharp and unwelcome disparity to the first game’s more freeform style of adventuring that went so far as to let players solve dungeons in (almost) any order they chose.

“All games I make usually get better in the development process, since good ideas keep coming, but Zelda II was sort of a failure,” Miyamoto admitted to Super Play,5 going on to say that he considers it “more of a side story about what happened to Link after the events in Legend of Zelda” than a canonical installment.6

Miyamoto and R&D4 — renamed Nintendo Entertainment Analysis & Development (EAD) — began prep work on the “true” sequel to Legend of Zelda in 1988, targeting it for release on the NES. But before development could get underway, a new competitor forced Nintendo to look ahead to the future.

**

If you enjoy Episodic Content, please consider showing your support by becoming a patron or via a one-time donation through PayPal.

Bibliography

- He was not yet ready: “Master of Play,” The New Yorker, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/12/20/master-of-play.

- went hiking and found a lake: Sheff, David L. Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered the World. (New York: Random House, 1993.)

- we tried to separate the different ideas: “Super Play Magazine Interviews Shigeru Miyamoto about The Legend of Zelda,” Nintendo Forums, http://www.nintendoforums.com/articles/40/super-play-magazine-interviews-shigeru-miyamoto-about-zelda.

- Zelda was the name of the wife: “In the Game: Nintendo’s Shigeru Miyamoto,” Amazon, http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/feature/-/117177/.

- games I make usually get better: “Super Play Magazine Interviews Shigeru Miyamoto about The Legend of Zelda,” Nintendo Forums, http://www.nintendoforums.com/articles/40/super-play-magazine-interviews-shigeru-miyamoto-about-zelda.

- more of a side story about what happened: Ibid.